Eric Garcia

Meghan Keane

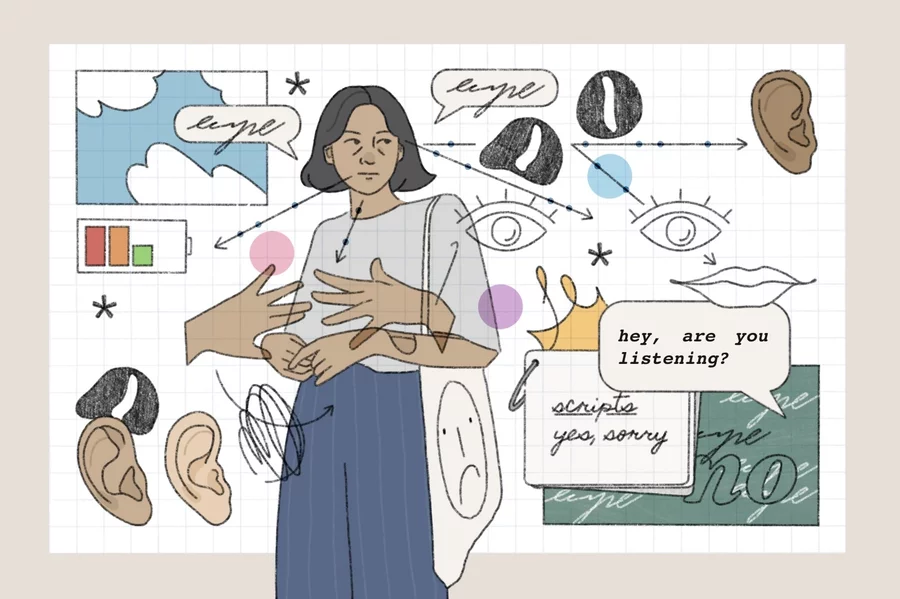

Masking is a common coping mechanism employed by autistic people in an attempt to fit into a neurotypical society. Examples of masking include forcing oneself to smile at the “appropriate” times, looking between someone’s eyebrows instead of making uncomfortable eye contact, and suppressing stims like hand flapping, even though they’re comforting. Megan Rhiannon for NPR hide caption

Masking is a common coping mechanism employed by autistic people in an attempt to fit into a neurotypical society. Examples of masking include forcing oneself to smile at the “appropriate” times, looking between someone’s eyebrows instead of making uncomfortable eye contact, and suppressing stims like hand flapping, even though they’re comforting.

Roughly 2% of adults in the United States have Autism Spectrum Disorder – that’s about 5.4 million people over the age of 18. And a lot of them go through their lives “masking.”

Social psychologist Devon Price explains that masking is any attempt or strategy “to hide your disability.” Price’s new book, Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity, explores masking, and how to “unmask” and live more freely.

In addition to hiding from others, Price says masking is also a coping mechanism. “You know that if you show your discomfort with eye contact, people will find you untrustworthy and treat you very differently,” he says.

Masking manifests itself in two ways: camouflage and compensation.

Camouflage includes behaviors like, “faking a smile, faking eye contact by looking in the middle of someone’s forehead,” Price says.

This is where compensation comes in. Price does this, for example, through scheduling ghost meetings on his calendar to give himself time to recharge.

“And that’s really what most masked autistics end up having to do, because a lot of us receive social input, our whole lives, that there’s something off about us,” he says.

While masking is employed by many autistic people, people in marginalized groups, including women, people of color and LGBTQ+ people might feel even more compelled to camouflage their disability.

“To this day, all of the assessments that we use for diagnosing autism, even in adults [are] still based on how to identify it in white cisgender boys, usually very young ones,” Price explains. “So what that means is, if you’re, let’s say, a young autistic black boy, you are far more likely to get diagnosed with something like oppositional, defiant disorder. You’re more likely to be seen as a behavior problem.”

“If you’re a girl, if you’re a person of color, if you’re gender nonconforming,” Price says, “you’re more likely to be seen as a problem to be contained.”

Price, who is transgender, compares it to how queer people are forced into a cisgender heterosexual world: Nobody chooses to be closeted, but they are born in the closet. In the same way, nobody chooses to wear a mask, but is born with a mask.

Devon Price is a social psychologist and the author of Unmasking Autism: Discovering the New Faces of Neurodiversity. Left: Photograph by Collin Quinn Rice; Right: Harmony hide caption

Shame is what drives autistic people to feel that they are flawed, failed and broken. Price says he used to go into a bathroom and hit his arms and legs with a hairbrush during sensory meltdowns.

“And I used to think that was something that was so disgusting and creepy and shameful about myself – that I was that out of control,” he says. Other autistic people manifest their shame through eating disorders, cutting themselves or substance abuse.

Price suggests two exercises to start unlearning shame:

“[For] most autistic people, we get the message from a really young age that we need to tone it down – that it’s weird to be too excited and too enlivened by the things that we care about, which is so sad,” Price says.

Conversely, expressing joy can be healing and get you back in touch with your true self.

Rekindle an old passion or find a new interest and experience complete joy around it. Find a community to experience that joy with you.

“It can be hard to drop all your inhibitions, but joy and pleasure and sharing that joy with other people – it just does so much to relax us and form authentic connections and to actually feel like, ‘Oh, life can be something I actually enjoy and look forward to every day,'” Price says.

Because autistic people often spend their whole lives trying to fit into a specific societal mold, it can be easy to lose touch with who you really are or what is really important to you. Price suggests trying the Values-Based Integration process, an exercise from autistic life coach Heather R. Morgan.

Price offers two steps to start this process:

To continue the process, Morgan suggests working with a licensed therapist.

Unmasking requires non-autistic people to be more inclusive and welcoming of their neurodivergent peers – whether they are autistic, have ADHD, Tourette’s syndrome, dyslexia or anything else.

Here are two important ways to be an ally:

The audio portion of this episode was produced by Meghan Keane.

We’d love to hear from you. If you have a good life hack, leave us a voicemail at 202-216-9823, or email us at LifeKit@npr.org. Your tip could appear in an upcoming episode.

If you love Life Kit and want more, subscribe to our newsletter.

Sponsor Message

Become an NPR sponsor